Josef Müller-Brockmann. 09 05 1914

Josef Müller-Brockmann: Rational Order and the Birth of the Swiss International Style.

Josef Müller-Brockmann (1914–1996) stands as one of the most influential figures in 20th-century visual communication. His pursuit of objective clarity and his systematisation of design through the use of the grid defined what would become known as the Swiss International Typographic Style — a visual language that continues to inform corporate identity, editorial systems, and user-interface design today.

Born on May 9, 1914, in Rapperswil, Switzerland, Müller-Brockmann studied architecture, literature, anatomy, psychology, and art history at the Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule (ETH Zurich) and the University of Zurich. This interdisciplinary education grounded his later work in structural logic and human perception — two dimensions that would underpin his design philosophy.

In 1936, he established his own studio specialising in exhibition design, commercial art, and photography. By the early 1950s, his commissions for the Tonhalle concert hall in Zurich began to crystallise the design language that would make him a central figure of modernist graphic design. His 1955 Beethoven poster — a study in rhythm, form, and typographic restraint — is often cited as a visual expression of musical abstraction and as an example of how design could operate as a form of visual composition analogous to sound.

Becoming a Designer by Accident

Müller-Brockmann often described his entry into design as accidental. Disinterested in writing as a student, he found comfort in drawing and visual composition. Encouraged by a teacher, he experimented with print and architecture before enrolling at the Zurich School of Arts and Crafts (Kunstgewerbeschule Zürich). His eventual realisation that design could fuse structure with expression reflects a defining tension of his career: the reconciliation of rational form with emotional resonance.

This biographical anecdote is instructive for students of design history: it shows how early 20th-century education still lacked a defined path for visual communication. The discipline was emergent — existing at the crossroads of fine art, architecture, and industry. Müller-Brockmann’s eventual discovery of the Bauhaus and Constructivism offered him a model for reconciling these worlds through functional aesthetics.

The Emergence of the Swiss International Style

Müller-Brockmann’s work coincided with post-war Europe’s desire for order, reconstruction, and universality. The devastation of the Second World War generated a cultural appetite for rational communication — a language that could transcend politics, borders, and ideology. The Swiss International Style emerged as a visual response to this context: clean, modular, and universal.

His influences included Constructivism (El Lissitzky’s use of geometry and typography to express social order), De Stijl(Piet Mondrian’s reduction of visual elements to primary forms and colors), Suprematism (Kazimir Malevich’s search for pure abstraction), and the Bauhaus (particularly László Moholy-Nagy’s and Herbert Bayer’s experiments with typography and photography). From these movements, Müller-Brockmann absorbed the idea that visual communication could embody the principles of modernity itself — clarity, precision, and rationality.

He co-founded the magazine Neue Grafik / New Graphic Design / Graphisme actuel in 1958 with Richard Paul Lohse, Hans Neuburg, and Carlo Vivarelli. The journal served as the intellectual manifesto of the Swiss movement, articulating its core principles: grid-based composition, sans-serif typography, asymmetrical layouts, and the designer’s role as a neutral transmitter of information.

Design as Objective Communication

Müller-Brockmann rejected the notion of design as a subjective or decorative act. He described his approach as the “suppression of the self in favor of the message.” His posters were not meant to express personal emotion but to clarifycontent. This concept resonates with the functionalist ethos that also guided modernist architecture and industrial design.

He famously wrote:

“In my poster, advertising, brochure, and exhibition creations, subjectivity is removed in favor of a geometric grid that determines the arrangement of words and images. The grid is an organisational system that makes the message easier to read.”

This systematic approach aligned with contemporary theories of visual perception and information processing — disciplines that were developing concurrently in psychology and semiotics. For Müller-Brockmann, communication was an act of translation: translating meaning into structure, rhythm, and proportion.

The Grid as a Philosophical System

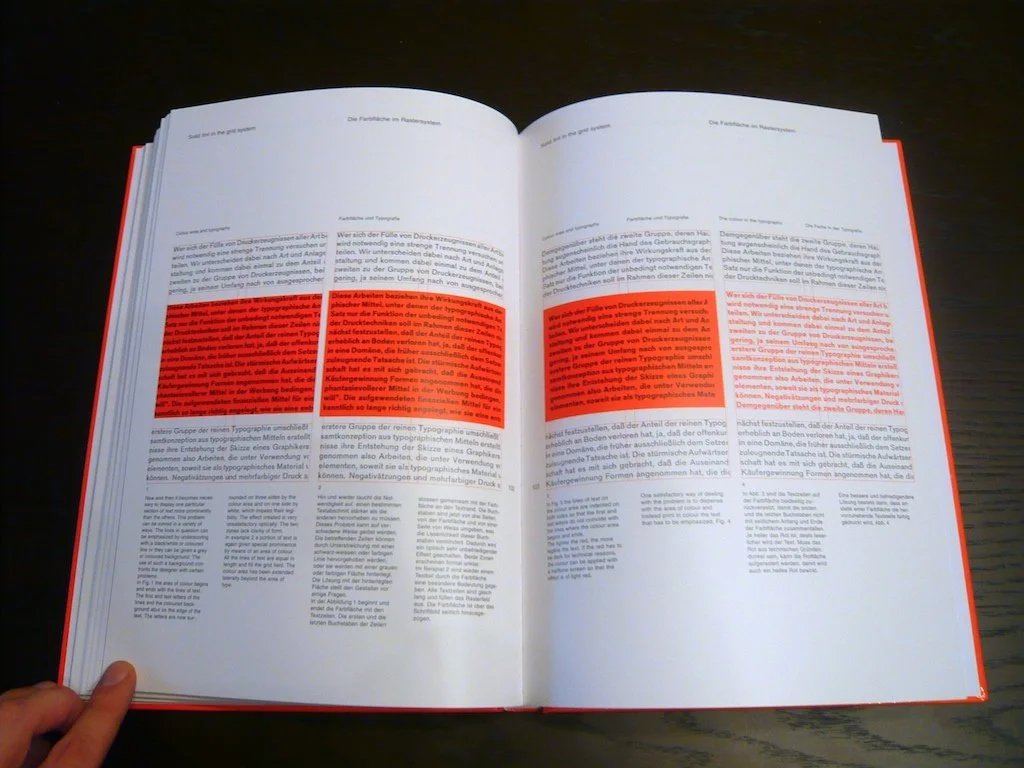

Perhaps Müller-Brockmann’s most enduring contribution is his formalisation of the grid system, most notably articulated in his seminal book Grid Systems in Graphic Design (1961). The grid provided a mathematical framework for ordering visual information, reducing design to a set of structural principles rather than stylistic impulses.

He wrote:

“The grid system is an aid, not a guarantee. It permits a number of possible uses, and each designer can look for a solution appropriate to his personal style.”

To interpret this pedagogically: the grid is not merely a technical tool but a philosophical stance. It reflects a belief in rational humanism — the idea that design should serve communication and understanding rather than self-expression. It is a visible manifestation of an invisible logic, a structure through which the designer achieves visual harmony.

In a broader academic sense, Müller-Brockmann’s grids anticipated systems theory and information design. His layouts echo mathematical ratios found in nature, architecture, and music — revealing how design could embody universal principles of order.

Musicality in Design

Müller-Brockmann’s poster series for the Zurich Tonhalle remains one of the most studied bodies of work in design history. He treated sound as an abstract form, translating rhythm and harmony into geometry. The Beethoven poster (1955) is often analysed through the lens of synesthetic design — the idea that different sensory experiences (sound and sight) can be expressed through shared structural principles such as rhythm and proportion.

Lars Müller, the publisher who later compiled Müller-Brockmann’s complete monograph, called the Beethoven poster “the ultimate example of musicality in design.” Its concentric circles are not literal depictions of music but metaphors for acoustic vibration and dynamic motion — demonstrating how abstraction can communicate emotion without resorting to representational imagery.

Rationalism vs. Expressionism

Müller-Brockmann’s insistence on legibility and order placed him at odds with the postmodern movements of the 1980s. He criticised designers like Neville Brody and David Carson for prioritising experimentation over communication:

“Some have set themselves the task of making typography unreadable… Illegibility seems to become an artistic project. I don’t want to read things like that.”

This debate between rationalism and expressionism continues to shape design pedagogy. Where Müller-Brockmann viewed design as a science of communication, postmodernists saw it as a cultural language open to reinterpretation. Both perspectives remain vital: one emphasising clarity and universality, the other cultural context and individuality.

Teaching, Writing, and Influence

In 1957, Müller-Brockmann succeeded Ernst Keller as professor of graphic design at the Kunstgewerbeschule Zürich, teaching until 1960. His teaching emphasised critical thinking through structure — encouraging students to view design as a process of reasoning rather than decoration.

His published works — The Graphic Artist and His Problems (1961), Grid Systems in Graphic Design (1961), History of the Poster (1971), and A History of Visual Communication (1971) — formalised the intellectual framework of modern graphic design. These texts became foundational in design education globally, shaping curricula from Switzerland to the United States, Japan, and beyond.

In 1967, Müller-Brockmann became a consultant for IBM, where his systematic approach to communication aligned perfectly with the brand’s need for global consistency. The rational corporate identity systems of the 1960s and 1970s — from Lufthansa to Braun — can be seen as direct descendants of his thinking.

Theoretical Implications and Contemporary Relevance

From a theoretical standpoint, Müller-Brockmann’s work exemplifies the modernist belief in universal communication— that visual form can transcend culture, language, and emotion through rational organisation. However, contemporary design scholars often revisit this notion critically. Postcolonial and feminist design theories challenge the assumption of universality, arguing that all communication is culturally situated.

Nevertheless, Müller-Brockmann’s influence endures not as dogma but as a foundation for critical engagement. His grid system remains embedded in digital interface design — from website layout frameworks to responsive grids in Adobe XD. The rationality he championed has found new life in the logic of code, algorithms, and design systems that underpin modern UX and brand design.

Legacy

Josef Müller-Brockmann died on August 30, 1996, in Zurich. His impact extends far beyond the posters and textbooks he produced. He transformed graphic design into a discipline grounded in thought, logic, and ethics — a bridge between art and science.

Today, his influence can be traced in every structured layout, every typographic hierarchy, and every systematised design framework. His insistence that “clarity and order are the means by which we give form to the complex” continues to guide both design education and professional practice.

Key Academic Insights

Rational Humanism:

Müller-Brockmann’s design is not purely mechanical but rooted in a belief in reason as a universal human trait.Semiotic Clarity:

His use of grids and typography embodies principles of semiotics — where meaning arises through structural relationships rather than decoration.Systemic Thinking:

The grid anticipates 21st-century system design — a framework adaptable to infinite iterations across media and platforms.Pedagogical Legacy:

His texts established design as an academic discipline, turning visual communication into a subject of inquiry rather than trade practice.

Recommended Readings for Further Study

Müller-Brockmann, Josef. Grid Systems in Graphic Design (Niggli, 1961)

Müller, Lars. Josef Müller-Brockmann (Lars Müller Publishers, 1995)

Rand, Paul. Design, Form, and Chaos (Yale University Press, 1993)

Hollis, Richard. Swiss Graphic Design: The Origins and Growth of an International Style, 1920–1965 (Yale University Press, 2006)

Meggs, Philip B. & Purvis, Alston W. Meggs’ History of Graphic Design (Wiley, 2016)